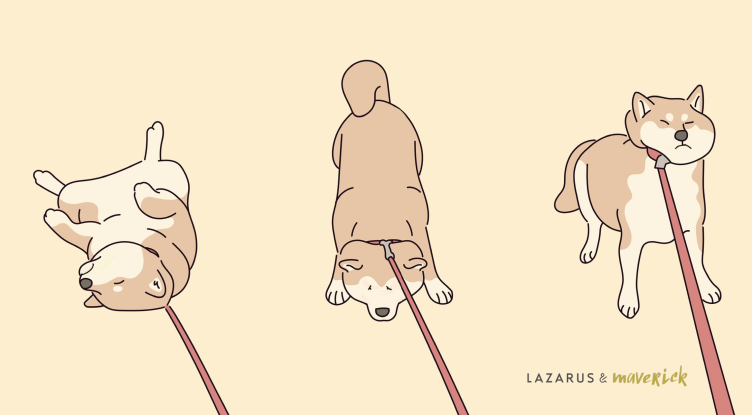

Disinterested. Indecisive. Resisting to move forward.

These are just some of the symptoms indicating that an employee might be overwhelmed and in the grip of an emotional toll caused by going through rough times.

Great leaders accept that it benefits everyone when they role model a positive mindset given that workplace emotions flow from a more socially dominant person to the less. Recognising the power of their leadership behaviours as the cause of follower emotions, they develop a habit of reflecting and adjusting their own unhelpful reactions first. However, even for transformational leaders, how they manage their emotions is only half of the story in the leader-follower emotional exchange.

One senior executive recently told me that while she was embracing being an empowering leader, some people on her team, six months into the pandemic, were now visibly fatigued: “It can be really hard when you know that you’re managing someone highly capable, but it’s a case of one foot in front of the other for them right now”.

One step forward, two steps back is not exactly the pivot formula which those tasked with adapting their organisations fast and furious are having in mind. Where there is a need to evolve to outsmart the marketplace conditions, negative emotions that kill progress and creativity can be a real deal-breaker.

While it is not the case with all employees, many leaders I have been speaking with lately confessed that they are now directly or indirectly managing someone who is either in a state of apathy, disengagement, passive-aggressive, impatient or stuck in a victim mentality. “Is it my job now to manage other people’s negative emotions too?” asked one senior executive.

Is it a leadership task to manage the followers’ negative emotions?

The answer is yes. It is good for employees’ wellbeing as it is for organisational health. According to one research on 163 leader-follower pairs, those employees whose leaders actively helped them manage negative feelings reported an increase in their overall job satisfaction and citizenship behaviours which include tasks outside of their job description. This could include “going the extra mile”, willingness to support their colleagues, refraining from gossiping, championing the business outside of workplace context.

What does Google, Pixar and NHS have in common?

A study of 180 teams working for Google identified that the one differentiating factor of highest-performing teams was the psychological safety felt by people. In practice, feeling safe to express thoughts and feelings without the fear of repercussions led to market breakthrough behaviours, better collaboration and innovation. For Ed Catmull, Pixar co-founder, the ability for people to speak up was the only way to build a billion-dollar creative business, but it was something that had to be intentionally ingrained in the daily culture. For example, in one futurespective exercise people were invited to answer the following question as if they were already years ahead in the future: “We’ve broken down barriers so that people feel safe to speak up. What did we do to achieve success?” Another profound evidence and case for supportive leadership can be found in a report on National Health Service in the UK which confirms a positive link between compassionate team leadership and a lower patient mortality.

Leading people and leading their emotions.

Whether employees are feeling frustrated about budget cuts, worried about deadlines, anxious about a client deal, angry about being unfairly treated, leaders play a part in managing these emotions.

The question that begs an answer is what active or conscious behaviours enacted by the leader can alleviate their followers’ negative mindset? How can this be done without draining the leaders’ own emotional reserves and done in a way that doesn’t turn a one-to-one update session into a counselling one?

Practical tips for leaders to help regulate others’ negative feelings:

If you want to help your employee reduce negative emotion, increase their motivation and job satisfaction, here are four proven behavioural strategies:

1. It’s ok not to be ok

When an employee expresses a negative emotion with the leader, the golden rule is to acknowledge it without adding own interpretation of it. Listen intently, hearing people out and showing positive regard for their emotional experiences, however unexpected or unreasonable these may seem to you, is crucial for making them feel validated and respected. It is their emotion and it is true to them.

When leaders suppress others’ negative emotions or disregard the validity of their feelings – “That’s a bit too much, don’t you think?” – it reduces the employee’s trust in the leader, and lowers both job satisfaction and positive discretionary behaviours.

2. Situation modification

As a leader show some flexibility and consider what can be changed about the situation itself that is causing an upsetting emotion in the follower. Goodwill creates good work.

If the employee is concerned about the deadline, can the timeframe be adjusted? Can parts of the project be reassigned to a colleague who is willing to help? In helping an employee regulate or reduce their negative emotion, it is crucial that the leader does not step into a blame culture or “I told you so” parent-child like dynamic, otherwise the negative emotion will be amplified.

3. Putting Problem into Perspective

This strategy involves leaders helping their employee see things in a new light. It is natural for employees to lose confidence from time to time, to make mistakes that snowball unhelpful assumptions.

This is particularly pertinent when people are overwhelmed and their brain starts to activate the involuntary fight, flight, freeze responses. Leaders who know how to help others reframe their problem and coach people out of a disempowering belief about the situation are perceived as transformational.

However, a leader must be careful to avoid adopting a role of a rescuer by diverting the attention away from the difficult issue – “Don’t worry about. I’ll sort it out” or “Focus on what’s going well”. While it’s well-intended and temporarily appreciated, it doesn’t empower the employee sense of agency and it removes the chance to expand their perspective about the upsetting event. The reaction to the problem lingers and so does the problem. Unsurprisingly, the research found that this tactic did not increase job satisfaction or citizenship behaviours.

The best strategies in this context are offered by mentoring and coaching skills. When done well, they can help turn chaos into order including the emotional cloud. They provide particularly useful frameworks and questioning techniques that help the leader maintain a healthy boundary between the leaders’ desire to help and the follower’s need for autonomy, accountability and resourcefulness. They also build trust between people respecting both the human and professional domain, realising vulnerability as a currency for growth. In my practice, I have also witnessed that trust-based relationship makes it feel safer for the employee to recognise when negative emotions start to engulf their mental health and they may choose to seek other support.

4. We’re In It Together – Team Culture

I remind leaders that leadership should not feel that all responsibility falls on their shoulders and their team is a mirror as well as the extension of the leadership function.

Team culture is a powerful management tool which can authentically inspire people towards collective excellence and high performance. I find that it is much easier to modify the distressing situation for one person when the entire team is on the same page and people feel that they have each other’s’ back. In a collaborative team, I’ve seen ideas flow pretty quickly about how to help one person manage a tough situation.

Creating an empowering team culture also serves as a health check for how things stand between individual team members and it helps weed out behaviours that can cause others stress and upset.

Team development sessions are great for both leaders and their teams to do a quick pulse check and answer questions such as “What do we need from each other to do great work here? What are our values and how do we know what they are? What are the desired and unwanted behaviours here? What is the right way for raising red flags”? When team coaching sessions are a regular fixture in people’s diaries, it helps everyone including those harbouring negative emotions in moving forward.

Leadership Legacy

Leadership is a tough act. Depending on how we behave as leaders, people either look up to us, look through us or look away from us. Good leadership happens when everyone looks in the same direction. Great leadership happens when people are also energised and excited to go in that direction. All of the leaders I have been speaking with over the past few months aspire to the latter. As their sounding board, I have every confidence in their ability to achieve this through their genuine interest to help others and to be of service not only on a good day but also in times of negative emotional experiences and personal crisis.

Author: Alex Lazarus, CEO & Senior Leadership Coach, Founder of Lazarus & Maverick, a global consultancy specialising in leadership development and transformation www.lazarusandmaverick.co.uk Source: Little, Gooty, Williams (2015), E.Catmull (2014)